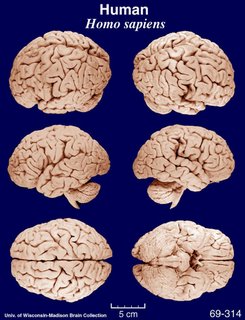

Wrinkles and folds on the brain

One of the first things people notice about the human brain is how convoluted its surface is. Instead of being smooth and nearly featureless like a kidney or spleen, the cerebral cortex (the thin layer of gray matter forming the outer surface of the brain) is chock-full of wrinkles and folds. Click on the image above for a larger view.

One of the first things people notice about the human brain is how convoluted its surface is. Instead of being smooth and nearly featureless like a kidney or spleen, the cerebral cortex (the thin layer of gray matter forming the outer surface of the brain) is chock-full of wrinkles and folds. Click on the image above for a larger view.Technically, each crevice is called a sulcus (pl. sulci) and each ridge between the crevices is called a gyrus (pl. gyri). Sulci and gyri are simply a way of increasing the surface area of the cerebral cortex (and therefore the number of neurons) without greatly expanding the size of the skull. Good thing, too - if our skulls were much bigger, they wouldn't be able to squeeze through the birth canal and C-sections would become the norm. Not to mention that those enormous heads would make us look like Hollywood aliens.

There are perhaps 30 or so named sulci and gyri, but learning to identify them - a time-honored task of every medical student - isn't as easy as it might sound. It isn't true that if you've seen one brain, you've seen them all. Although the total surface area of the cortex is roughly the same in all people, there are large variations in the size of particular areas. Whether these differences in area are related to differences among individuals in various skills and functional capacities is largely unknown (but there have been a few intriguing studies, such as this one and this one).

For the sake of all those sleep-deprived med students, why can't we have a brain that looks more like, say, a howler monkey's?

So nice and smooth, almost no sulci or gyri to memorize. Actually, we humans start out wrinkle-free early in development. Check out this brain from a fetus at 22 weeks:

So nice and smooth, almost no sulci or gyri to memorize. Actually, we humans start out wrinkle-free early in development. Check out this brain from a fetus at 22 weeks: As neurons continue to divide, grow, and migrate, the cortex folds in on itself, forming a recognizable but unique pattern of bumps and grooves. Unless you happen to have lissencephaly. Children born with lissencephaly (which means "smooth brain") are severely retarded and many die before the age of 2.

As neurons continue to divide, grow, and migrate, the cortex folds in on itself, forming a recognizable but unique pattern of bumps and grooves. Unless you happen to have lissencephaly. Children born with lissencephaly (which means "smooth brain") are severely retarded and many die before the age of 2.So we should be happy with our brain wrinkles. As I've often pointed out to my students, it could be worse. We could be dolphins:

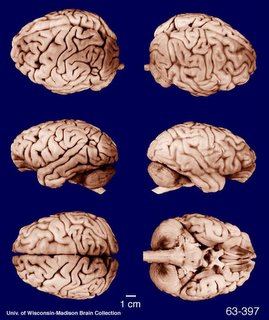

Finally, here's a quiz. Compare the brain below to the brain at the top of this post. What's wrong with it?

Answer: nothing, if you're a chimpanzee. Clearly, there are anatomical differences between a chimpanzee brain and a human brain, particularly in the size of the prefrontal cortex (the front part of the cerebral hemispheres). But the similarities in brain anatomy, like the similarities in DNA, are striking.

Answer: nothing, if you're a chimpanzee. Clearly, there are anatomical differences between a chimpanzee brain and a human brain, particularly in the size of the prefrontal cortex (the front part of the cerebral hemispheres). But the similarities in brain anatomy, like the similarities in DNA, are striking.All but one of the brains shown here belong to the University of Wisconsin and Michigan State Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections. I modified the first and last images slightly to make them easier to compare. The fetal brain came from humanpath.com.