Why do men have nipples? In women, of course, the major function is clear: nipples provide a convenient milk-delivery device for a hungry infant to latch onto. Nature has even made it easier for babies to find the nipple by causing the areola to turn darker during pregancy. (At least that's one explanation; personally I think mothers are pretty good at guiding babies to the nipple with or without the additional color contrast.)

In men, however, the nipples serve no obvious function. They certainly have nothing to do with delivering milk. Lactation has never been observed in any healthy male mammal. I had to qualify that last statement with "healthy" because there are diseases, such as certain tumors of the pituitary gland, that can cause men to produce milk, an inconvenient condition called

galactorrhea. An imbalance in the endocrine system can also cause

gynecomastia, enlargement of the male breast. Still, these are rare exceptions to the rule. Nipples and breasts may have the

potential to be useful in men, but in general they appear to be extraneous.

So why do we have them? Could male nipples be vestigial organs, evolutionary equivalents of the appendix? Darwin proposed that male mammals once shared the job of providing milk to their young. It's delightful conjecture, and not unreasonable, but it remains in the realm of just-so stories because (so far) there is no way to test its validity. If the story were true, you might expect the most anatomically primitive mammals -

monotremes such as the duck-billed platypus and echidna - to have males with more highly developed nipples. In fact, we see the opposite: monotremes - male and female - have no nipples at all (but the females still lactate, expressing milk via little pores in the skin). I'm only aware of a couple mammal groups in which the female has nipples and the male doesn't (a feature we might call "mammillary sexual dimorphism"): horses and rodents. If male nipples are on their way out, they sure are tenacious.

Whether or not male nipples are a relic of evolution, they are almost certainly a relic of development. In the earliest weeks following conception, the male and female embryo follow a virtually identical developmental trajectory. Then at about 7 weeks, the production of testosterone kicks in and the male diverges anatomically from the female. By then it's too late: nipples have already formed in both sexes. Biologically it's conceivable that random mutations could reverse the continued growth of the male nipple, causing it to involute and disappear completely by the time the baby boy is born, but apparently there hasn't been pressure for such mutations to take hold, if they have occurred. There

are occasional mutations that lead to the

absence of one or both nipples (in both males and females), but they are typically associated with other defects such as missing muscles and sweat glands and webbing of the fingers.

So are male nipples utterly useless? It's hard to respond with an unqualified "yes," because someone can always come up with something plausible. In some men the nipple may be considered an "erogenous zone," but what part of the male anatomy isn't? Even the appendix, the poster child of vestigial organs, isn't totally useless: it contains an abundance of lymphocytes and other cells that fight infection. Still, as many

appendectomy patients can attest, we can live perfectly well without it. The same goes for nipples in men.*

In the interest of gender equity, what about women? Do women have anything similar to a male nipple, an essentially useless part of their anatomy that reflects a developmental constraint? In a classic (1987) and controversial essay called "Male Nipples and Clitoral Ripples," the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould argued that the clitoris, along with the female orgasm, fits the bill. The argument is further elaborated in a recently published book by biologist and philosopher of science Elisabeth A. Lloyd:

The Case of the Female Orgasm: Bias in the Science of Evolution. Evidently she makes a good case (click

here for a review), but lingering doubts are understandable. I suspect that the average woman places a much, much higher value on her clitoris than the average man places on his nipples.

Instead of weighing in on that controversy, I'd like to propose a better female analogue of the male nipple: the

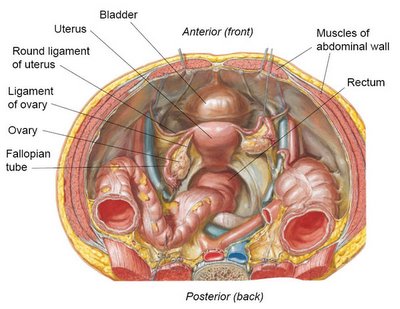

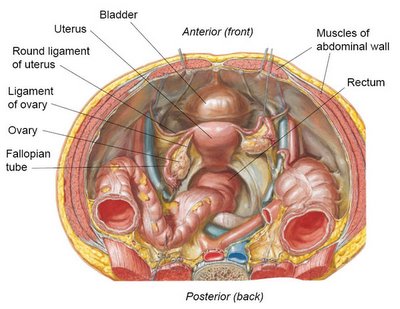

round ligament of the uterus. The round ligaments are two slender ropes of connective tissue that run from the top of the uterus to the front side of the abdominal wall, pass through the

inguinal canal (approximately at the level of the bikini line), and ultimately blend into the fatty connective tissue of the

labia majora.

In the female fetus, you can trace the round ligament from the abdominal wall all the way up to the ovaries. At those early stages of development the round ligament is referred to as the

gubernaculum, which means

governor (same root as

gubernatorial). The male fetus has a gubernaculum, too, except that it's attached to testes, not ovaries. As the fetus grows, the role of the gubernaculum is similar in both the male and female: it gently guides the gonads (i.e., testes or ovaries) during their descent from their birthplace in the upper part of the abdomen. As they descend, the gubernaculum gets shorter.

There the similarities end. The testes have much farther to go. While the ovaries drop down into the relatively well-protected pelvic cavity (the space surrounded by the hip bones), the testes travel onward, punching a tunnel (i.e., the inguinal canal) through the abdominal wall and ending up suspended in an outpouching of the abdominal wall called the

scrotum. Click

here for a little animation of the testes squeezing through the abdominal wall (the greenish band is the gubernaculum).

The different fates of the ovaries and testes are reflected in the gubernaculum. In the male, each gubernaculum shortens as much as possible and leaves little or no remnant in the scrotum. In the female, the middle of the gubernaculum fuses with the top of the uterus, forming what appear to be two separate ligaments: (1) the

ligament of the ovary, which connects the ovary to the uterus, and (2) the

round ligament of the uterus, which connects the uterus to the abdominal wall. See the illustration below.

The ligaments of the ovary may serve a useful function: each one appears to maintain the proper distance between the ovary and the uterus, so that the fallopian tube can receive eggs from the ovary during ovulation.

But the round ligaments? As far as I can tell, they're useless. One popular (and generally trustworthy) online resource (

The Interactive Body Guide) suggests that the "round ligaments hold the uterus

anteverted (inclined forward) over the urinary bladder." Seems reasonable, until you realize that something like 20-30% of women are born with a uterus that is

retroverted (inclinded backward). The retroverted configuration is considered a perfectly normal variation that has no effect on fertility. In other words, the round ligaments aren't very good at holding the uterus forward because there's no good reason for them to be.

Not only are round ligaments unnecessary, they can be a real pain - literally. As the uterus grows during pregnancy, the round ligaments stretch like rubber bands and tug on the abdominal wall, often causing

round ligament pain. Fortunately the pain can usually be relieved with simple measures such as a hot bath, a shift of body position, or Tylenol. Like male nipples, the round ligaments of the uterus are relatively minor anatomical flaws, and any inconvenience they cause pales in comparison to the many anatomical marvels of the human body.

*More resources on male nipples: